SINOPSE

CONTOS ESTRANHOS – Edição bilingue. Contos e Novela. O livro se compõe de 35 contos e uma novela intitulada O Homem do País que Não Existe. O autor mantem-se na linha do realismo mágico, tendência literária contemporânea, tão querida na América Latina. A novela trata de um personagem que, após fazer a barba, vê-se surpreso em não estar no próprio país, um lugar que não se encontra no mapa e causa polêmicas profundas na população que o acolhe.

FORTUNA CRÍTICA - ERIK VAN ACHTER

The Poetics of the Unexpected. A Review of Eduardo Mahon’s Contos Estranhos. Weird Tales. Cuiabá: Carlini & Caniato Editorial, 2017.

Erik Van Achter

KU Leuven (Belgium)

CLP (Coimbra – Portugal)

Short stories and particularly short “short-stories” have it that they impose the most intolerable typographical restriction upon talented writers who seek to create an entire universe, invariably aiming to impress the reader. Moreover, contrary to short stories, tales – the generic label Eduardo Mahon rightfully opted for in his title – belong to an earlier stage in the genre’s evolution. They bathe in orality, embracing such sub-modes as the unrealistic, the imaginary and the uncanny, frequently following long standing traditions in fantastic literature, reviving famous mysterious “clichés” to be found in the works of the early masters (Chaucer and Boccaccio). Eduardo Mahon’s Weird Tales, differ from most other similar short fictions due to a specific manner of writing and the astounding capability to maintain the reader’s attention to the very last full stop.

Owing to the genre’s imitated orality, Mahon in his Contos Estranhos, Weird Tales, wrote unique stories, which exhibit the absurd, pretend to be real, while using a vast number of both literary and linguistic devices. In more learned terms, and relying on Canadian scholar Northrop Frye (Anatomy of Criticism), Mahon’s Contos Estranhos, Weird Tales combine the “romance” and the “novel” modus, an extremely difficult combination, and yet one which Mahon turns into a complete (post-modern?) success! The exquisite use of a most varying array of storytelling strategies, engaging word choices, and exceptional plots make the tales by Mahon outstanding literary pieces worth a discussion and an analysis beyond the scope of the present review.

Each of the tales boast features, which help the reader to classify Weird Tales according to the manner, style, language, and other linguistic and stylistic peculiarities. Reading these tales, it is hard to deny that they were not purposely written in style even if on the face of it, some seem to merely follow the standard procedure of traditional tales or, at times, even of children’s stories. Lucinda Nogueira Persona summarizes it all perfectly well in her “afterword” to the English translation of Mahon’s stories when she writes that “The fictional field conceived by Eduardo Mahon comprises the lives of simple people governed by basic needs, e.g.: making both ends meet [...]” (Persona, 2017, p. 354). First of all, it is necessary to mention some peculiarities in the stories’ composition, which were made in a primitive and/or an apparent simplified way. They have a beginning, a middle and an end and each sentence apparently follows each other sentence, just like any human being not endowed with the gift of fiction writing would tell it, would write it down. On closer inspection, while reading the tales, the reader understands that the “simplicity” of the storytelling, which is created by means of short sentences and monosyllabic words imitating the spoken word, conceals intricate narration which only surfaces when the reader has finished and is left alone pondering over what he or she has read. In “Maternal Instinct” e .g. this process is very visible in the opening paragraph: “Thirty years raising Ducks. That is what Mr. And Mrs Torquato did all their lives. They lived in a small ranch near many small towns and they delivered the duck eggs to the duck lovers, who were very few in the beginning”(Mahon, 2017, p. 268). In “There’s Nothing to Complain About” it is possible to find sentences like “Cheng Wu was a happy person. He was forced to be happy, so to speak” (Mahon, 2017, p. 253). The word choice, which from the first view may seem to be directed to a “child-reader”, in reality, targets on adults, as the author widely used expletives and a complex problematic. For what does it mean, being “forced to be happy”. And, how very handily has Mahon downplayed his first statement by simply adding “so to speak”.

Despite the numerous syntactic variations (to be understood as the author’s stylistic peculiarities or preferences), other classical short stories by Poe or even Hemingway come to mind during the reading process. They differ from Mahon’s tales, both in message and in themes discussed, even though their theories would easily apply. For indeed, Poe’s dictum that the first sentence of a text piece should already irreversibly lead to the final effect, and Hemingway’s so-called Iceberg Theory could have been Mahon’s source of inspiration as to his craft. However, one can hardly imagine E.A. Poe writing as for example in the story “The Hernia” “Holy crap! Don’t piss me off!” (Mahon, 2017, p. 245). As to Hemingway... I wouldn’t know.

All these aspects made the stories of Mahon unique and engaging literary pieces. What happens when a hernia turns into a child? (“The Hernia”). What about a human fetus suddenly emerging from a goose egg? (“Maternal instinct”). And how does it feel if you are born Caucasian and a slow but irreversible bodily transformation changes your ethnic status? (“The Black sheep of the Family”) Or, when your right eye starts spinning around? (“Irene’s Right Eye”) Do you only then see reality? Something more than reality? A Surreal reality? Or, probably a magical reality? These are the questions which haunt the reader, who upon reaching the surprise ending of each story steadily realizes that none of the traditional labels apply. Is Miguel Cervantes in “Cervantes’ Tears), just anybody, coincidently bearing the same name as the Spanish writer? Is he the re-incarnation of the Spanish Writer? Or just a modern hack happily using the well-known name? Maybe it is merely a post-modern bricolage of the writer himself?

The unexpected transition from ordinary to absurd, from concrete to suddenly abstract is most weird (weird stories, indeed!) in Mahon’s stories. They usually begin average and then, following the initial “ordinary” manner of storytelling, the author describes unbelievable and bizarre things, which he presents without any hesitation and specific attitude. Mahon himself said in an interview:

The plain style is a typical feature of mine, from Nevralgias onwards. Even in poetry, I try to be as direct as possible. I believe that the more cleaned-up, the better a contemporary text is. Now, with a few changes, I am bringing single-paragraph tales that deal with a magical world, impossible situations, unusual existences.The novelty of the experiment lies with the ‘Man of the Country Which Does Not Exist’, where each paragraph is a chapter, a puzzle form at a very fast pace” (http://www.olhardireto.com.br) (my translation)

Reading Mahon, inevitably makes the informed reader think of other and similar weird short stories in western literature: Michael Chabon, Jorge Luis Borges, Ray Bradbury, Ben Okri, to name only a few. However, finding a common ground is not so easy. Excepting perhaps, Okri, Eduardo Mahon is much more a storyteller than a literary craftsman, blunt and direct; no labyrinths, or hidden mirrors, only stammering surprises at the end, but only after an unstoppable stream of (manicured beforehand?) stock phrases as can be seen at work in “The Bookstore”

The boy who left the tram was called Bob Parker. He was one block away from his friend’s house. He came to a dead end as he realized there were no houses there, he came across a second-hand bookstore. However, it was not precisely the store that called his attention. (Mahon, 2017, p. 253)

The poetics of the unexpected in the tales of Mahon is performed via the sequence of events, impossible to predict. In other words, the author builds his stories without any logical structure of event sequence, which would help a reader to predict the final of a story. At the beginning of a tale, the reader cannot even imagine how it would end. For example, “The Color Thief” (Mahon, 2017, p. 247) concludes with a fantastic and absolutely unexpected episode, and even with the help of another protagonist. On the other hand, the story “The Unrecognizable Ernesto Fuentes” (Mahon, 2017, p. 256) does not even have an appropriate closure or finale; as a reader is “suspended” in suspense, literally!

Another peculiarity, mentioned earlier, consists in the realistic appearance of the world. Thus, the author does not create some imaginative or a fantasy world for his stories; he does not even mention the affection of some mysterious or supreme forces on his characters. Mahon adds abnormal and strange things to the everyday realities, even without any accentuation on the weirdness thereof. The world in which his characters live seems to be normal, and the fantastic events are the part of its “normality.” Part of this normality comes from scientific and mathematical reference points. Mahon likes to mention doctors incapable of solving the mysteries, Mahon does not forget that mankind likes to measure, i.e. use a very consistent metric system like in “There’s Nothing to Complain About”. One single bed, one small wood table, three shirts, two pairs of jeans, etc. While we count (as Mahon seems to know all too well), we are being had, for we trust human expectations which always take place in the realm of the logical and the causal. When the room closes in on Cheng, Mahon makes the main protagonist count and measure: “When he entered, he knew the walls were getting closer [...] he measured every corner of the room and he wrote down the figures on the palm of his other hand: one meter and half” Suddenly the reader has to ask himself/herself: “What is this all about” and shortly thereafter: “And what if?”. What if indeed rooms could grow smaller. And this “what if” in Portuguese “E se” is exactly Mahon’s motto (https://www.carliniecaniato.com.br/eduardo).

Finally one minor aspect needs to be mentioned. I made the tactical decision to discuss Mahon’s Weird Tales in the English translation which goes with the Brazilian Portuguese original set of stories. I did so, because I believe Mahon’s stories have a right to become world literature, i.e. to leave their Portuguese speaking homelands and to be translated not only in English but hopefully in a myriad of other languages! However, the old adage warns us: “traduire, c’est trahir un peu”. Unfortunately, this is also what happenedwith the translation of Contos Estranhos. The tales read better, much better, in the original Portuguese. It is not always a matter of linguistic incompetence on the part of the translator, but the chronotope of a genre called tale is too specific to the region and the imagination that goes with it, to be easily translated. Future translations better have a serious introduction commenting both on the translation and the genre.

References

Carlini & Caniato Editorial/Tanta Tinta Editora (https://www.carliniecaniato.com.br/eduardo).

Accessed 02.01.2018 (Publisher’s Website).

Mahon, E. (2017). Contos Estranhos. Weird Tales. Cuiabá: Carlini &Caniato Editorial.

Mercuri, I. (2017). Mahon Lança livro de Contos de literatura fantástica em MT, MS e na Europa.

https://www.olhardireto.com.br (assessed 03.01.2018).

Persona, L. N. (2017). Afterword. In Mahon, E., Contos Estranhos, Weird Tales (pp. 351-353).

Cuiabá: Carlini & Caniato Editorial

OLGA MARIA

UM DEDO DE (BOA) PROSA

O compromisso com o próprio estilo define a arte

(E.M.)

Não é nada fácil perseguir o ritmo de produção do escritor Eduardo Mahon, carioca radicado em Cuiabá-MT há mais de três décadas. Articulista, advogado e professor, tem-se destacado no meio literário pela capacidade de instigar e manter um dedo de prosa (e poesia) com o leitor.

Contos estranhos é o seu 7º livro publicado. O que não é pouco no curto espaço de tempo entre eles. Costuma dizer que escreve para ser lido, para formar leitores. Comprometimento social com a arte que o mantém atualizado, também, nos meios virtuais. Não fala só de literatura, mas do hoje e do outrora e, principalmente, fala sobre arte, criatividade, desejos de transformação social e de atitudes ousadas que coloquem o livro nas mãos dos jovens. E tem conseguido. Seus textos atingem os limites do desejável para um novel escritor. É um dos que mais se comunica com o leitor em potencial pela forma como distribui e faz circular sua obra. Certamente está contribuindo para a configuração da cadeia sistêmica que envolve meio social, história, produção e formação, como aquela traduzida por Antonio Candido e repensada por críticos e teóricos contemporâneos. Isso tudo com a base de uma consciência política partilhada por meio da qual as veleidades mais profundas do indivíduo se transformam em elementos de contato entre os homens e as interpretações das diferentes esferas da realidade.

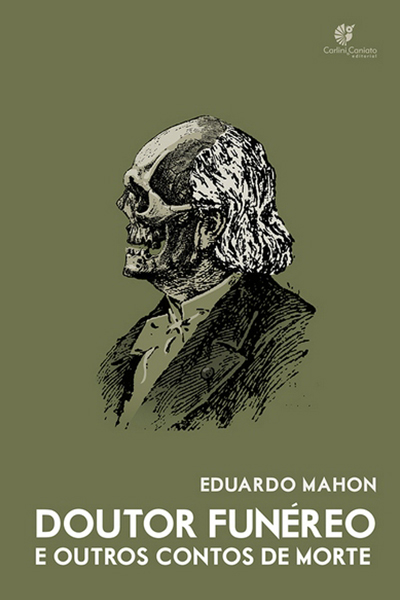

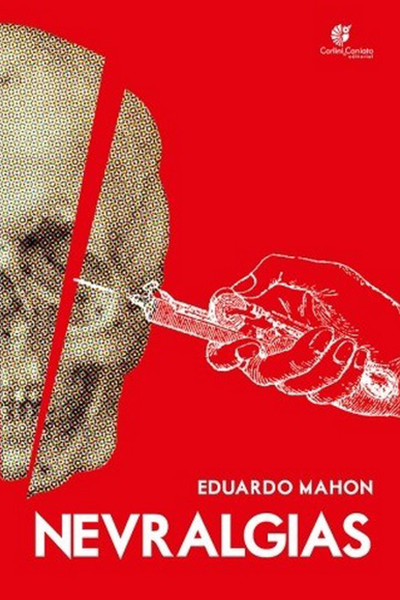

Num recuo em câmera lenta sobre o conjunto da produção narrativa de Mahon, que beira à sequência fílmica, revejo as crônicas, intermediadas por poemas, de Nevralgias (2013), na mortífera contação de Doutor Funéreo e outros contos de morte (2014), na romanesca de O cambista (2015) e O fantástico encontro de Paul Zimmermann (2016)1. Nessas obras, a lente capta os fotogramas que recompõem o jogo entre o figurativo e o linguístico transformado pela sensibilidade do escritor. Deles me utilizo para (re)construir alguns dos múltiplos sentidos destes Contos estranhos que em boa hora, chegam ao público. Tarefa mais de leitor enredado nas malhas do texto que de crítico, lembrando Silviano Santiago ao propor a relação livre de uma teleologia, mas prenhe das novidades inesperadas que vão além da ruptura e da negação. Minha vontade é que, pelas vias do desconforto ou da acomodação, as misteriosas tramas destes Contos estranhos agucem a imaginação para novos textos, para os intertextos que recheiam sua (boa) prosa, pois há um percurso de produção que não é casual para o leitor e, talvez, não o seja para o escritor, mas fundamenta o espaço simbólico em que se dá a representação literária. Encanta-me o domínio da totalidade dos textos de Mahon pela qual me chega a estratégia do escritor, seus subterfúgios, seus mecanismos estruturais, suas experimentações, seus topoi, tão necessários ao estatuto do ficcional.

Tanto no inesperado desfecho de Hérnia, O olhar de Irene, O irreconhecível Ernesto Fuentes, O caso de Mário Curi, ou no quase momento etéreo de A menina que roubava cores, Contando estrelas, Instinto maternal e Uma nova estética, o que oscila são elementos do intangível, da loucura do mundo contemporâneo, do jogo do olhar: “No percurso, viu-se, pelo retrovisor transformar-se seu Carlinhos completamente negro, de nariz largo e os cabelos crespos” (A mancha da família, grifo meu). À uma imagem subjaz outra(s) mediante processo mediático de experiência do espaço, numa espécie de figuração que expõe o efeito poético. A beleza do conjunto submete os dados materiais à ficção: “Queria ter asas. Sonhava voar [...]. o olhar de Schüller era multifacetado: enxergava num ângulo muito mais aberto do que estava acostumado” (A nova condição de Ibsen Schüller, grifos meus).

São 25 contos em que o inusitado desarma o leitor. Estrutura e conteúdo se unem num estilo poético-narrativo que é a própria essência do seu criador. Criador e criatura constituem um coronário. São artérias irrigando emoções e sensações, hora de confortante humor, hora de insólitos efeitos, próprios do movimento estonteante do gênero que, aqui, se condensa em estrutura mínima (quase minimalista!) do exercício da criação. Como se atendesse ao leitor do jornal, o instantâneo é flagrado no momento mesmo da criação: “comendo um repasto de mulherio como nunca antes, viu-se enredado numa espécie de maldição” (Morpheu maldito). Sem subterfúgios, mas coloridos; sem romantismo, mas saborosos e plenos de fluidez rítmica. Uns aproximam-se da contação com cadeiras na calçada, conversas ao rés-do-chão, como em É hoje, Uma nova estética, O encosto, O hóspede; outros, encostam-se ao pé-de-orelha do leitor, como em A mancha da família, O homem que sabia de tudo, A adoção dos Moura Furtado, Segunda Feira.

Os fotogramas tecidos em poucas linhas congelam “quadros” integrados (ou não) à disposição do olhar leitor. O resultado é certa simbiose palavra/imagem que a memória se incumbe de complementar/desconstruir num jogo criativo em que a palavra se dá, sem tréguas, ao leitor: “É que, à noite, a solitária médium entregava-se aos prazeres da carne com as tentações dos espíritos” (O encosto, grifo meu). Palavra nua, livre e fina, condensada no sentido enxuto, cujas angulações captam personagens simples transformadas em figuras e fatos insólitos e misteriosos que recriam universos tecidos pela aparente anomalia e pelo fantástico de uma literatura de tentáculos que se lança (enlaça) para novos e inusitados níveis de relação: “O pobre homem percebeu que, mesmo sabendo de tudo, não havia o que fazer com tanta informação” (O homem que sabia de tudo, grifo meu). Assim, são sobrepostos os focos da lente pelas aproximações e (aparente) distanciamento.

O crítico de arte Giulio Carlo Argan lembra que é enquanto problema dotado de uma perspectiva histórica que uma obra sobrevive porque é constantemente revisitada, ressignificada pelo juízo contemporâneo. Então, a melhor forma de ler um texto é interrogá-lo, dar voz a ele, pois os sentidos estão no que poderia ser e não no que é: “Aos poucos assumiu a nova feição e passou a frequentar o trabalho da mesma forma como andava em casa – calça jeans e camiseta justa, um sapato feminino de salto baixo, além de esmalte, batom e cabelo comprido com escova diária” (Uma nova estética, grifo meu). A direção do olhar é, portanto, o imperativo poético e cognitivo que pressupõe a capacidade humana de assimilar a densidade histórica. Olhar e mente se sintonizam.

Onde reside, então, o elemento perturbador? Talvez nos confusos vestígios do “eu”, na imaginação e no pensamento humano e/ou no seu apagamento pela ruptura do óbvio, pelo exercício linguístico e pelo predomínio de uma aguçada veia crítico-humorística. Pelas possibilidades imagéticas, o que é ritual se dessacraliza e os tabus são remexidos a ponto de se confundirem na dupla dose do linguístico e do filosófico.

Desta forma, os Contos estranhos são, ao mesmo tempo, visual e plástico, anima/alma do dizer, moldura e enquadramento, tudo na correta medida do gênero escolhido. Sem torpor, mas com estranheza e fino humor. Um enigma para o leitor, (des)fazendo a dupla representação de ser e parecer.

O risco desta aventura é um irrecusável convite à leitura!

Olga Maria Castrillon-Mendes

Professora e pesquisadora da literatura/UNEMAT-Cáceres.

Cadeira n. 15/AML

1. Em 2015 publica, ainda, a trilogia poética Meia palavra vasta, Palavras de amolar e Palavrazia vista, no conjunto da obra, como laboratório da sua prosa-porosa que absorve a agilidade do verso.